Seeking Authenticity: A Journey through Art, Iconography, and the Face

- Details

- Published: 11 September 2023

- Hits: 610

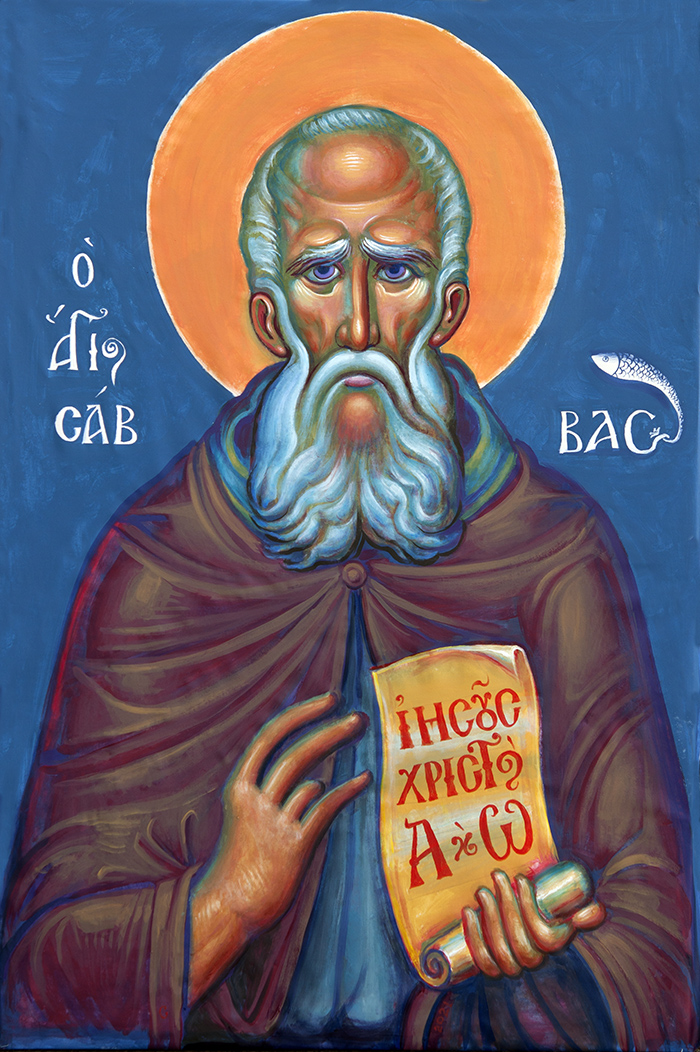

Fr. Stamatis Skliris

When we are on the bus and we arrive at the bus station, we see genuine faces and glances. Nevertheless, cinema and fashion have instructed people to be pretentious and to adopt a fake manner of standing, speaking, and moving. This constitutes an alienation of the human person. As an artist, I strive to discover the real humanity. We have even lost the scent of carnation. The sellers of carnation say that the scent is gone, even though the form remains the same. It is carnation in the form, but it is not full since it has no particular scent. As an iconographer, I have to depict a saint. The saint is a man who stands before God and before his fellow man with love. He is in a state of confession. Me too; I am in a state of confession at this moment. I am trying to express what is my problem. As the ancient philosopher Diogenes said, “I am searching for a man.” Indeed, we are searching nowadays for a man who does not seek one’s self-interest, who is not cunning and devious. We are accustomed to playing roles; honesty is thus tricky. One way would be to depose the masks we are searching for and find the true “me.” And if I find the true me, I can see the true “you”.

What does this mean from the point of view of artistic language? In art, one works with line and color. And with some axes that one can trace by pencil and then cover. The goal is to depict movement and expression, especially the expression of the eye. I think that one should not map all the possible codes of movement and color but let the possibility for something arise beyond the rules. Let me phrase it in another way. When I paint the halo of a saint, if I construct it with the help of a compass, the halo will be identical to the one constructed by any other artist who could trace a perfect cycle. One cannot thus depict the particular expression of a concrete person. But every person wants to be loved in a special, unique, and unrepeatable way, not in terms of general categories. For example, I am not just your doctor; I am this particular doctor. What is thus meaningful is to let the compass aside and not abide by the general rules of sketching and coloring according to perspective and the relations between light and shadow. This would be tantamount to being in a state of blindness.

When he wakes in the morning, the artist takes his brush and creates a portrait in a completely unexpected way. Pablo Picasso studied this issue and stated: “If I knew in advance the outcome of my painting, then I would stop painting.” Henri Focillion says: “Oh, brush stroke, you battle with destiny in order to achieve rare novelties.” The artist is alone with his brush before the canvas. The canvas is the destiny; the fate is to depict human beings. For example, a man who gets out of jail. How would such a man be? The brush stroke has to portray some particular strange trait that would make him unique, for example, in the person’s eyebrows.

The meaning of icon painting is the transcendence of the rules of icon painting. One should not follow the rules of harmony in the architecture of the human face and body, such as that the face is one-eighth of the body. As an icon painter, one should not be restricted; it could be the one-ninth or anything one wants. Of course, the icon painting is shaped by the wisdom of centuries of tradition. But this wisdom has been crystallized in unyielding deterministic rules. One could forget such rules for a while, act as if drunk, and allow for something uneven. The errors of the iconographers should be respected. The famous artist Soutine was distorting the human face and the houses. He could depict one village with bent houses. It is the eye that should be clear, especially the iris.

Personally, I have introduced the element of the instantaneous in iconography, even though the iconography aims to depict what is eternal. How, then, could the instantaneous be introduced? God is eternal. But I, as a human being, am changeable. The eye might be eccentric. For example, when the Mother of God stands below the cross and observes the crucifixion of her Son, she says: “I kept everything that You said as divine, and now I observe You dying! But I do believe that You are indeed the Son of God.” To depict such moments, one needs expressionism. That does not mean an expressionist grimace, such as in the art of Edvard Munch, because this could lead us to a demonic element. The icon painter could never wish to introduce the demonic element into iconography. But let us think about the state of the Mother of God when she was evangelized by the archangel Gabriel. She was just a kid of seventeen years old. The archangel Gabriel told her that she would give birth to the Son of God, to which she replied: “I am the servant of God. Let Thy will be done!” She was a woman, a girl devoted to God and wanted to fulfill the divine will.

As we live in the present secular era, we cannot say what the saints observe in their visions. But we can witness the saintly transformation in their face and body. Edgar Allan Poe had one described the predicament of a man who had once fallen in a hurricane. His hair had become white, and his eyes were twisted. If God was revealed to saint Porphyry, then the saint is changed and has some wondrous features. What is that? It could be his cheeks that are swollen, expressing his eternal joy. Saint Porphyry once said that the state of a man who is in paradise was revealed to him by God. This is a state of joy that is incomparable to any kind of worldly joy. This is what I call the “visionary” element. I also depicted Saint Nectarios of Aegina. I did not portray him as similar to his photography. I portrayed him as a child would have done, as a small child who takes his crayons, being sure about himself. At another time, I made a figure caricature with one feather and called it “the Mohican.” The visionary consists in painting something not as it is at the particular historical moment but as it is formed through a divine transfiguration.

In pictorial language, this is expressed by the paradoxical character of the colors and the distortion of the forms. Distortion should not be understood in a sense of terror. One should not be terrorized when seeing a saint. But, for instance, if at one time, when you were scolded at school, your father had specially glanced at you, this is something different from what ordinarily happens. In the same way, an icon of Saint Nectarios must have something other than his photo, which depicts the mortal state of existence. Eternal life is the transcendence of the absolute determinism of natural laws. We all want to fly, yet we fall. We all want to traverse walls, yet we break our heads. The resurrected Christ is the one who managed to traverse the closed doors. An iconographer should strive to represent this: The condition of the resurrected Christ who has crossed the closed doors. The icon of Christ is full of light; it has a light structure. The forehead, the nose, and the cheekbones are structured through light. Whatever exists partakes in light. This is something very different from the situation in which Christ is under a tree and the shadow covers half His face.

There are also some lines called “psimythia,” which are like the rays emitted by the face of Christ in the Transfiguration when it shone like the sun. How can one look at a man who shines like the sun? This should be depicted in a way that is different from being lighted upon by a spotlight. And yet, there is also something similar. The saintly light falls upon the Christ and makes Him shine. This is the condition of the transfigured man.

The issue at stake is the difference between the photo, which depicts the instant, and the icon. The photo shows the exterior of the face and its harmony; that is the reason between the length and the breadth of the face, the size of the eyes, etc. The icon chases away the shadows. The face of Christ or of the saint cannot be in the darkness. The icon painter is trying to depict a vision of the beings that are not observed as such in daily life. This is a significant risk because the figure must not only be ecstatic. It is instead a divine alteration as the one suffered by Christ at the moment when he was illuminated with the uncreated divine light on Mount Thabor. According to the Gospel, His face shone like the sun, and genuine humanity was revealed in His person. At that moment, Christ was innocent. We are not like that. For example, when the professor is asking a student to hand him over a book, the latter might have a servile expression. When Christ was in contact with His Father and was shining due to this relation, there was no pretension in Him whatsoever.

For this reason, we speak about “apophaticism”. One cannot say, “he was tall, he was short, he was thusly, he was red, etc”. But we speak in an apophatic manner: “He was unpredictable, He was transcendent, He was a continuous surprise.” The Fathers have developed such an apophatic language according to which God is invisible, uncircumscribed, etc.

My problem is, for example, how to paint a woman without the pretension that we find in models: a woman from my village or my neighborhood who has no pretension. Love would then mean a relation to a human being that is unique and unrepeatable independently from objective properties. I can love a human being that is not beautiful or moral. This happens many times. One loves a man who turns out to be wicked. We are interested in the humaneness of this human being, in the lack of cunningness. A child who says, “Mummy, I have not eaten the cake,” is without cunningness whatsoever. Apophaticism strives to express this lack of cunningness and pretention.

Man is unique and unrepeatable in so far as he is an image of God. When a man becomes selfish, competitive with others, or strives to become a god by his own forces, he loses his humanity. And he finds it again when he glances at the one he loves as a unique and unrepeatable being. He says, “I love you,” meaning, “I love you as you are.” If a beautiful girl has many admirers, but something happens to her face, and she becomes ugly and abandoned, she would cry and say: “I thought they were coming because of me and not because of my beautiful eyes.”

The saints see Christ as a man with no lie or pretension in Him. The difference between God and man is that man has many kinds of lies within him, as when we are pretending. Death is the biggest lie. One can say that he is strong, and then he might fall or faint at another moment. One cannot explain how this can be depicted. For example, the Pantocrator seems, on the one hand, to be a very strong man and, on the other, very caring for the one who observes Him. I try to show the same thing in icons by depicting a saint bending over the faithful. I think this gives us some criteria to compare the present of the photo to the eternity of the icon. It is very crucial for the painter to have lived what he describes and to be simple-spirited. In the iconography, the clothing and the face lines are simple.

As I said in the beginning, the clothing and the lines of the face should be simple. The eyes should be without pretention and their iris should be looking at us. This is expressed in two ways: on the one hand through the sketch and the lines, and on the other, through the color and the light. The light falls upon the face of Christ. Thus, The nose throws a shadow on the cheek, and Christ’s chin and beard throw a shadow on the throat. This means that someone on the outside offers Christ His light. It is God the Father who shines upon His Son. He transcends the universe even though he is omnipresent inside it. He is above everything and outside everything, but simultaneously, He enters history and shines upon His Son because He loves Him. Alongside His Son, He loves every human being. Therefore, the saint should have the characteristics of Christ.

There is thus the following movement. The one is shining upon the other, and the enlightened saint is now shining upon the faithful venerating him. When we look at the Mother of God, the Christ, or Saint Nectarios, they are all full of light. This is what the Church is trying to manifest: the mystery of iconography, namely the relation between the persons. Nothing is unrelated. Christ visited the fields, the sea, and the boats of his illiterate disciples. He was full of love. It is said that he had extreme love for John, his beloved disciple. And the disciples loved Him back. Peter stated that he was ready to fall to fire for Him, but Christ warned him about his future betrayal. But all the disciples had later fulfilled their oaths of love since almost no apostle died of natural causes.

In iconography, love is expressed through light. This is not just a symbolism. It is an immediate presence. The Father loves His Son and shines upon Him. The Son loves man and shines upon him. One can relate that to our feelings: When your mother or any beloved person loves you, she brings you joy. When she is indifferent, she brings sorrow. What is joy in human feelings is expressed not just through symbols but through a way of painting concerning the divine condition. This way of painting is relative to the light. First, one paints a dark layer, the “proplasmos,” and then uses lighter colors for the cheeks, the nose, etc. The light gives existence to non-existent beings. The metropolitan John of Pergamon (Zizioulas) said that the darkness of the proplasmos is the non-being before God created the universe. The light, equivalent to God’s love, says: “Let there be a man”. “Let there be Adam and Eve” forms a type of painting with no room for death. From a pictorial point of view, we have what one can say in French, “pleines formes,” concerning especially the hands and feet. The forms are round. Everything is enlightened. Nothing is in the shadows. Everyone is standing before the houses. At the Last Supper, one shows the house where it took place, but the table with the Lord and the disciples is like standing before it, in a sort of courtyard. One could say that the light expresses some kind of giving love to one another. The houses and the trees are enlightened. Observe the trees in the image, in the icon of the Assumption, for instance, or in the icon of Jesus’ prayer at Gethsemani, which takes place at the Mount of Olives. Each tiny leaf is enlightened but the tree in its entirety is also enlightened.

In this way, nature has a preponderant role through its being illuminated. This is created through color. The shadows are also colored. Have you thought about that? The impressionist movement had discovered this in 1880. But Christian art had already known it since the icons of the 4th century when Constantine the Great had allowed for the building of churches and making mosaics in Ravenna and Santa Maria Maggiore. This is a light without ending. There is no sunset; the light is shining upon everything forever.

If I am allowed to formulate this in an extreme way, I could say: “There is no drawing.” Give me a blackboard, and I can create the form of the saint by enlightening both the surroundings and the interior. However, some exercise takes place since every iconographer remains a portraitist. He is drawing the portrait of Christ. But this is a portrait after the Resurrection. It was not a portrait at the time of the Crucifixion when Christ was in blood, losing His light and exclaiming, “My God, why have Thou forsaken me?”. On the contrary, the iconographer depicts Christ at the moment of the divine glory, in Thabor as well as in the Resurrection. In his drawing exercises, in his sketches, the iconographer will paint you or another person and thus use shadows and the relative laws of nature. But when he will try to raise you to the level of divine likeness, he will try to show how you are equal to God and, therefore, shining like Christ. The angels who were present at Christ’s tomb and had moved the stone had garments shining like lightning.

The exercise of drawing is just a stage. The iconographer might observe some models. The specialists say that the ancient Greeks were not using models. The statues had all the details in an idealized way. Divinity was identified with the ideal of the form. But these ideals point to the past, to the beauty that exists from time immemorial. In Christianity, Christ is the absolute surprise, whereas ancient philosophers like Socrates focused on the present and the past. For example, one can see the bus station, the exit of two persons at the port, or the dance at one party. When I was young, at one party in Tambouria, Piraeus, I opened a door and saw a donkey. They had one donkey closed in one room, and while we were dancing, bossa nova, the donkey was looking at us with humble eyes. This made me think of the donkey that was introduced to the holy icon of the Birth of Christ when the Mother of God was holding Him in her embrace. Even the donkey partakes of the divine light. This is a structural light, that is, a light that is carrying the forms. I might make a thousand drawings with my pencil to discover each person’s particularity. We need that in this temporary life. But the icon takes us to the other life. This means that we take the drawing and put light on the forehead, in the nose, etc., and we will thus transform the drawing into a sort of painting that is structured through light.

The rhythm is not created through axes. The rhythm is formed through the uncreated light that creates the whole of creation, including the little bird on the branch of the tree, the little leaf, the tile in the courtyard, the water in the creek, the form of the father, and the face of the saint. This expresses the entire creation and man at its peak. It expresses the love of each person for the other, a love that makes each person unique and unrepeatable. For this reason, Christ never ceases to love us, even when we commit the greatest crime. He has even taken the grateful thief to paradise. There is always hope, and one should never say that he is alone.

Athens, September 11, 2023

Όταν είμαστε στο λεωφορείο και φτάνεις στη στάση και βλέπεις διάφορα πρόσωπα, διάφορα βλέμματα είναι φυσικά εκείνη την ώρα γιατί κάτι πρέπει να προλάβουνε και βγαίνει φυσικά ο εαυτός του. Μερικές φορές, όμως, ο κινηματογράφος και η μόδα μας έχει μάθει μερικές κατηγορίες ανθρώπων να φτιασιδώνονται και να υιοθετούν έναν τεχνητό τρόπο να στέκονται, πώς θα μιλήσουν, πώς θα κινηθούν και αυτό αλλοτριώνει το ανθρώπινο πρόσωπο. Εγώ τώρα ως εικαστικός διψάω να βρω τον άνθρωπο. Είναι σαν αυτό που χάσαμε το άρωμα από τα γαρύφαλλα. Όσοι πουλάνε γαρύφαλλα λένε ότι χάθηκε το άρωμά τους, ενώ η μορφή τους είναι η ίδια. Είναι γαρύφαλλα, αλλά δεν είναι ολοκληρωμένα γαρύφαλλα, αν δεν ευωδιάζουν. Σαν αγιογράφος πρέπει να φτιάξω έναν άγιο. Ο άγιος είναι ένας άνθρωπος που επειδή βρίσκεται μπροστά στον Θεό, μπροστά στον άλλο άνθρωπο με αγάπη, υπάρχει κάτι το εξομολογητικό σε αυτόν. Κι εγώ αυτή τη στιγμή εξομολογητικά μιλάω, λέω ποιο είναι το πρόβλημά μου. Είναι όπως ο Διογένης έλεγε «ψάχνω άνθρωπο να βρω». Πράγματι σήμερα ψάχνουμε να βρούμε άνθρωπο χωρίς ιδιοτέλεια, χωρίς δόλο, έναν ανιδιοτελή άνθρωπο. Κι επειδή έχουμε μάθει όλοι να παίζουμε ρόλους, είναι δύσκολο. Ένας τρόπος θα ήταν ο καθένας μας να αποβάλει τις μάσκες που φοράει και να βρει τον πραγματικό «εμένα, τον Σταμάτη». Ίσως αν βρω αυτό, να μπορώ να βρω και τον πραγματικό εσένα.

Σε εικαστική γλώσσα τώρα πώς γίνεται αυτό; Έχουμε να κάνουμε με γραμμές και με χρώματα. Και με άξονες νοητούς που μπορούμε να φτιάξουμε με μολύβι και τους σβήνουμε μετά, ώστε η κίνηση να φαίνεται, η έκφραση, και κυρίως η έκφραση του ματιού. Αν μπορέσουμε να μην κωδικοποιούμε όλους τους κώδικες και τους άξονες, αλλά να αφήσουμε να υπάρχει κάτι στραβό. Να το πω αλλιώς. Φτιάχνω ένα φωτοστέφανο. Αν πάρω ένα διαβήτη και το φτιάξω θα είναι ίδιο με αυτό που μπορούν όλοι να πάρουν ένα διαβήτη και να φτιάξουν έναν τέλειο κύκλο. Άρα δεν θα αποδίδει την ιδιάζουσα έκφραση του συγκεκριμένου προσώπου. Κι ο κάθε άνθρωπος θέλει να τον αγαπάνε σαν κάτι το ιδιαίτερο, το μοναδικό και ανεπανάληπτο. Και όχι σαν μια κατηγορία. Λ.χ. είμαι ο γιατρός σου. Είμαι ο γιατρός σου ο τάδε. Λοιπόν το νόημα είναι να μην κάνω τον κύκλο με τον διαβήτη, να μην κάνω το σχέδιο με βασικούς κανόνες χαράξεως και να μη βάζω το χρώμα με βασικούς κανόνες φωτοσκίασης και προοπτικής. Αυτό για να επιτευχθεί θα είναι σαν να είναι κανείς σε κατάσταση τυφλώσεως. Ξύπνησε το πρωί και παίρνει το πινέλο και του βγαίνει το πορτρέτο όπως δεν το περίμενε. Ο Πικάσο το είχε μελετήσει αυτό και έλεγε «αν ήξερα τι θα βγει από αυτό που κάνω, θα σταμάταγα να ζωγραφίζω». Κι ο Ανρί Φοσιγιόν λέει «Ω πινελιά, εσύ αναμετριέσαι με το πεπρωμένο, για να του αποσπάσεις σπάνιες καινοτομίες». Δηλαδή η πινελιά έχει μπροστά της τον καμβά. Ο καμβάς είναι το πεπρωμένο, η μοίρα μας είναι να φτιάξουμε τον άνθρωπο και αυτός ο άνθρωπος βγήκε από τη φυλακή. Πώς είναι αυτός ο άνθρωπος. Η πινελιά βρίσκει κάτι το περίεργο στο φρύδι του στο μάτι του και αυτό τον καθιστά κάτι το μοναδικό.

Η αγιογραφία είναι το να καταργήσω τους κανόνες της αγιογραφίας. Δεν πρέπει να υπακούει στους κανόνες αρμονίας της αρχιτεκτονικής του προσώπου και του σώματος. Ας πούμε το πρόσωπο πρέπει να είναι το 1/8 του σώματος. Βάλε το 1/9, κάνε ό,τι θέλεις, ξέχνα το αυτό, μη δεσμεύεσαι. Η αγιογραφία από τους πολλούς αιώνες έβγαλε σοφία. Αλλά η σοφία αυτή αποκρυσταλλώθηκε σε κανόνες ντετερμινιστικούς, ανένδοτους. Ξέχνα τους για λίγο, σαν να είσαι μεθυσμένος, και άσε να βγει κάτι στραβό. Τα λάθη μας για τους αγιογράφους είναι κάτι σεβαστό και ο Σουτίν, ο διάσημος ζωγράφος, ζωγράφιζε παραμορφώνοντας το πρόσωπο, παραμορφώνοντας τα σπίτια, ζωγράφιζε ένα χωριό με παραμορφωμένα σπίτια. Πρέπει το μάτι να είναι μεγάλο και καθαρό. Η ίριδα. Εγώ εισάγω και το στιγμιαίο, το ενσταντανέ. Η αγιογραφία βέβαια είναι κάτι το αιώνιο. Πώς θα μπει το ενσταντανέ; Τι σχέση έχει; Κι όμως. Ο Θεός είναι κάτι το αιώνιο. Εγώ ο άνθρωπος μεταβάλλομαι. Μπορεί το μάτι να είναι και κάτι παραποιημένο. Ας πούμε είναι η Παναγία κάτω από τον Σταυρό και βλέπει τον Υιό της να σταυρώνεται και λέει «Εσύ που εγώ φύλαγα όλα όσα έλεγες και ήταν θεϊκά και τώρα βλέπω να πεθαίνεις! Σε πιστεύω, όμως, ότι είσαι Υιός του Θεού». Αυτό για να γίνει πρέπει να μπει εξπρεσιονισμός. Δηλαδή μια μικρή παραμόρφωση, αλλά όχι με τη μορφή γκριμάτσας, όπως κάνει ο Μουνκ, γιατί αυτό μας πάει σε κάτι δαιμονικό. Ας μη το πούμε δαιμονικό, γιατί δεν κάνει, ο ζωγράφος που ζωγραφίζει δεν θέλει να κάνει κάτι δαιμονικό. Αλλά η Παναγία, πώς ήταν όταν την ευαγγελίστηκε ο αρχάγγελος Γαβριήλ; Μια παιδούλα δεκαεπτά χρονών. Της λέει θα γεννήσεις τον Υιό του Θεού. «Ιδού η δούλη Κυρίου. Γένοιτό μοι κατά το ρήμα Σου». Είμαι ένα κορίτσι του Θεού. Ας γίνει το θέλημά Σου.

Επί της ουσίας εμείς δεν μπορούμε εδώ σε αυτή τη ζωή να πούμε τι βλέπουν οι άγιοι. Τι βλέπουμε εμείς στους αγίους. Βλέπουμε μια αλλοίωση. Πώς λέμε κάποιος έπεσε σε έναν τυφώνα; Ο Έντγκαρ Άλλαν Πόε λέει ότι κάποιος έπεσε σε έναν τυφώνα και βγήκε με κάτασπρα μαλλιά και γένια και τα μάτια του έτσι. Αν, λοιπόν, αποκαλύφθηκε ο Θεός στον άγιο Πορφύριο κάτι έχει. Τι έχει; Για μένα είναι τα φουσκωμένα μαγουλάκια του που έχει πάντα χαρά. Και λέει «μου αποκαλύφθηκε ένας άνθρωπος που ήταν στον παράδεισο. Ο Θεός μου το αποκάλυψε. Και ήταν τόσο χαρούμενος μα τόσο χαρούμενος που δεν έχω δει ποτέ τόσο χαρούμενο άνθρωπο». Αυτό το ονομάζω εγώ «οραματικό». Ζωγράφισα τον άγιο Νεκτάριο. Δεν τον έκανα όπως τον έχει η φωτογραφία του, αλλά λίγο τον ζωγράφισα όπως θα τον ζωγράφιζε ένα παιδάκι που παίρνει το παιδί τα κραγιόνια με μια σιγουριά στο χέρι του και κάνει και λέει. Εγώ έκανα μια καρικατούρα και βάζω από πάνω ένα φτερό και λέω «ο Μοϊκανός». Λοιπόν, οραματικό είναι αυτό που δεν είναι ακριβώς όπως ήταν στη συγκεκριμένη ιστορική στιγμή, αλλά ήταν αλλοιωμένο από μια θεία αλλοίωση.

Στην εικαστική γλώσσα αυτό το εκφράζουμε με την παραδοξότητα των χρωμάτων και με την παραμόρφωση των σχημάτων. Αλλά όχι παραμόρφωση να τρομάζουμε που βλέπουμε τον άγιο. Ας πούμε αν ο μπαμπάς σου εσένα κάποια στιγμή που σε είχαν μαλώσει στο σχολείο σε αγκάλιασε και σε κοίταξε, αυτό το μάτι του είναι κάτι που δεν το είχε τις άλλες μέρες. Το ίδιο και ο άγιος Νεκτάριος πρέπει να έχει κάτι που δεν το είχε στη φωτογραφία του που είναι προς θάνατον. Η αιώνιος ζωή είναι η υπέρβαση του απόλυτου ντετερμινισμού των φυσικών νόμων. Δηλαδή όλοι θέλουμε να πετάμε, αλλά πέφτουμε. Όλοι θέλουμε να περνάμε μέσα από τον τοίχο, αλλά σπάμε το κεφάλι μας. Ο Χριστός πέρασε κεκλεισμένων των θυρών. Ε, άμα ο Χριστός πέρασε κεκλεισμένων των θυρών, βρες εσύ που είσαι αγιογράφος, βρε άνθρωπε, έναν τρόπο να Τον δείξεις. Η αγιογραφία του Χριστού έχει το φως. Δηλαδή βάζει φως, φωτοδομή. Αυτά που δομούν το φως, δηλαδή το μέτωπο, τη μύτη, τα μήλα, τα δομεί με βάση το φως. Δηλαδή πρέπει ό,τι υπάρχει να έχει φως. Όχι να είναι ο Χριστός κάτω από ένα δέντρο και να πέφτει σκιά και να του σκιάζει το μισό πρόσωπο. Κι όταν το κάνουμε αυτό και βάζουμε και μερικές γραμμές που τις λέμε ψιμύθια και είναι οι ακτίνες που βγάζει το πρόσωπο του Χριστού στη Μεταμόρφωση όπου «έλλαμψεν το πρόσωπον αυτού ως ο ήλιος». Πώς μπορούμε να δούμε έναν άνθρωπο να λάμπει όπως ο ήλιος; Αλλά να μην είναι και σαν να του ρίξαμε έναν προβολέα; Έχει όμως κάτι από προβολέα. Δηλαδή το άγιο φως πέφτει και Τον κάνει να αστράφτει. Και αυτό είναι ο μεταμορφωμένος άνθρωπος.

Το πρόβλημα που τίθεται είναι η διαφορά ανάμεσα στο ενσταντανέ της φωτογραφίας και στην εικόνα. Τι διαφέρει η εικόνα από τη φωτογραφία. Η φωτογραφία δείχνει εντελώς το εξωτερικό του προσώπου και τότε είναι όλα αρμονικά. Δηλαδή το πλάτος επί το ύψος πρέπει να έχει έναν λόγο, το μάτι πρέπει να είναι τόσο και ούτε μεγαλύτερο ούτε μικρότερο. Η εικόνα, όμως, πρώτα πρώτα διώχνει τα σκοτάδια. Όπως είπαμε, δεν μπορεί να είναι μισοσκιασμένο το πρόσωπο του Χριστού ή του αγίου. Και, κατά δεύτερο λόγο, αποτυπώνει με τα πινέλα και με τις πινελιές μια κατάσταση οραματική ότι δεν έχουμε ξαναδεί αυτό το πράγμα μέσα στην καθημερινή ζωή. Τώρα εδώ είναι μια σχοινοβασία που κάνει ο αγιογράφος, γιατί μπορεί να φτάσει να τον κάνει σαν αλλοπαρμένο. Είναι μια αλλοίωση που την ώρα εκείνη ο Χριστός φωτιζόμενος με το θείο φως πάνω στο Θαβώρ και με το να γίνεται αυτό που λέει το Ευαγγέλιο «έλαμψεν το φως αυτού ως ο ήλιος», εκείνη την ώρα βρήκαμε τον πραγματικό άνθρωπο στο πρόσωπο του Χριστού. Δηλαδή την ώρα αυτή ήταν αθώος. Ενώ εμείς, λ.χ. «για δώσε μου το βιβλίο», λέει ο καθηγητής. «Μάλιστα κύριε καθηγητά», εμείς παίρνουμε ένα δουλικό ύφος. Ενώ ο Χριστός την ώρα που επικοινωνούσε με τον Πατέρα Του και τον έλαμψε ο Πατέρας Του, ήταν ο ασχημάτιστος. Η λέξη «ασχημάτιστος» σημαίνει ότι δεν ήταν δήθεν. Δηλαδή δεν πήρε έναν ψεύτικο σχηματισμό το πρόσωπό Του. Αυτό, όπως καταλαβαίνετε είναι κάτι που αποφατικά κατανοείται. Δεν μπορούμε να πούμε «ήταν ψηλός, ήταν κοντός, ήταν έτσι, ήταν κόκκινος». Αλλά λέμε αποφατικά «ήταν απίθανος, ήταν απρόβλεπτος, ήταν άπαιχτος ο Θεός». Αυτό το «άπαιχτος» είναι αποφατική διατύπωση και οι Πατέρες έχουν αναπτύξει αποφατική θεολογία: Ο Θεός είναι αόρατος, απεριχώρητος κ.ο.κ.

Το πρόβλημά μου είναι να ζωγραφίσω μία κοπέλα χωρίς να είναι στημένη όπως τα μοντέλα, χωρίς να είναι βαμμένη. Είναι μια κοπέλα του χωριού μου, της γειτονιάς που δεν προσποιείται τίποτα. Και, αν την αγαπήσω, εκείνη την ώρα αγαπάω έναν άνθρωπο ως μοναδικό και ανεπανάληπτο ανεξαρτήτως από τις ιδιότητές του. Δηλαδή μπορεί να αγαπήσω έναν άνθρωπο που δεν είναι όμορφος. Μπορεί να αγαπήσω έναν άνθρωπο που δεν είναι ηθικός. Πόσες φορές συμβαίνει. Αγαπάμε και μετά βγαίνει να είναι σκάρτος. Αλλά πάλι εδώ μας ενδιαφέρει η ανθρωπιά αυτού του ανθρώπου, δηλαδή να βρεθεί σε μια στιγμή αυτός ο πονηρός άνθρωπος που να του βγει ότι είναι άδολος, χωρίς δόλο. Όπως το παιδάκι που λέει «μαμά, δεν έφαγα εγώ το γλυκό». Ενώ έχει φάει το γλυκό. Είναι άδολο το παιδί, δεν έχει την πονηρία να κάνει δήθεν ότι δεν ξέρει τίποτα για το γλυκό. Αλλά πάει και το λέει. Ε, αυτό τα λέει όλα, αλλά αποφατικά. Ο νοών νοείτω.

Σύμφωνα με αυτά που λέμε, λέμε με άλλα λόγια ότι ο άνθρωπος είναι μοναδικός και ανεπανάληπτος, επειδή είναι εικόνα του Θεού. Και την ώρα που βγάζει την ιδιοτέλεια, τη συμφεροντολογία, το να θέλει να πει κάτι που δεν έχει πει κανένας άλλος, το να θέλει να είναι σαν Θεός, χάνει την ανθρωπιά του. Και την ξαναβρίσκει, όταν κοιτάζει αυτόν που αγαπάει σαν μοναδικό και ανεπανάληπτο. Του λέει «σε αγαπάω». Αλλά του λέει «σε αγαπάω έτσι όπως είσαι». Αν μαζεύονται γύρω από μια όμορφη κοπέλα διάφοροι νεαροί και την αγαπάνε κι αυτοί, ο μη γένοιτο, πάθει κάτι το πρόσωπό της και ασχημύνει και την εγκαταλείψουν κλαίει τραγικά γιατί λέει «εγώ νόμιζα πως ερχόντουσαν για μένα, για αυτό που ήμουν, όχι επειδή είχα ωραία μάτια».

Οι άγιοι έφτασαν σε ένα σημείο που βλέπουν τον Χριστό ως άνθρωπο, αλλά έναν άνθρωπο που δεν έχει καμία ψευτιά μέσα Του. Η διαφορά ανάμεσα στον Θεό και στον άνθρωπο είναι ότι ο άνθρωπος έχει πολλά είδη ψευτιάς που μπορεί να συμβαίνουν όταν καμωνόμαστε κάτι. Η μεγάλη ψευτιά είναι ο θάνατος. Το να λέμε ότι ζούμε και εγώ είμαι δυνατός και αύριο πέφτω κάτω, ας πούμε, λιπόθυμος. Αυτό είναι ένα πράγμα ανεξήγητο, πώς θα το εξηγήσουμε εικαστικώς, αλλά είναι αυτό που έχει ο Παντοκράτωρ να φαίνεται από τη μια παντοδύναμος, δηλαδή είναι ένας δυνατός άνδρας, και από την άλλη να βγάζει ένα νοιάξιμο για σένα που τον βλέπεις. Κάνεις έτσι και τον βλέπεις και είναι σαν να σκύβει από πάνω σου. Πολλές φορές ζωγραφίζω εικόνες που είναι λίγο γερμένος ο άγιος, για να δείξουμε αυτό το πράγμα. Λοιπόν, αυτό νομίζω ότι μας δίνει κάποιο μέτρο, για να συγκρίνουμε το τώρα, τη φωτογραφία, με το αιώνιο, την εικόνα. Από ζωγραφική πλευρά παίζει πολύ μεγάλο ρόλο να το έχει μέσα του ζήσει ο ζωγράφος, να έχει δηλαδή μια στοιχειώδη απλότητα καρδιάς, θα έλεγα συγκεκριμένα ονόματα ανθρώπων που συνεργαζόμαστε. Έχω έναν άνθρωπο που είναι πολύ απλός. Να έχει, λοιπόν, έναν τρόπο που να έχει απλότητα. Όπως είπα στην αρχή, τα ενδύματα να είναι απλά και οι γραμμές του προσώπου να είναι απλές. Το μάτι να είναι όσο το δυνατόν πιο ανεπιτήδευτο και η ίριδα να μας κοιτάει. Αυτό εκφράζεται με δύο τρόπους, αφενός σχηματικά με το σχέδιο, με το σκίτσο, με τη γραμμή. Αφετέρου, χρωματικά με το φως. Δηλαδή, το φως πέφτει και φωτίζει το πρόσωπο του Χριστού. Η μύτη ρίχνει στο μάγουλο μια ερριμμένη σκιά. Και εγώ μπορεί να έχω αυτή τη στιγμή μια ερριμμένη σκιά εδώ. Και το πιγούνι του Χριστού και ο πώγων ρίχνει μια ερριμμένη σκιά στον λαιμό. Αυτό σημαίνει ότι κάποιος απ’ έξω Τον φωτίζει. Δηλαδή ο Θεός Πατήρ φωτίζει τον Υιό Του. Είναι επέκεινα του σύμπαντος. Είναι βέβαια και πανταχού παρών μέσα. Αλλά Αυτός που είναι πάνω απ’ όλα και έξω απ’ όλα μπαίνει μέσα στην Ιστορία και φωτίζει τον Υιό Του, επειδή τον αγαπάει. Και μαζί με τον Υιό Του αγαπά και κάθε άνθρωπο και έτσι ο άγιος πρέπει να έχει τα χαρακτηριστικά του Χριστού. Έτσι έχουμε μια κίνηση: Ο Ένας φωτίζει τον Άλλο και ο φωτισμένος φωτίζει τώρα τον πιστό που τον προσκυνάει. Την ώρα που κοιτάμε την Παναγία, τον Χριστό, τον άγιο Νεκτάριο είναι φωτεινός. Έτσι είναι ζωγραφισμένος, γιατί αυτό θέλει να δείξει η Εκκλησία. Και αυτό είναι το μυστήριο της αγιογραφίας. Δηλαδή η σχέση μεταξύ των προσώπων. Δεν υπάρχει τίποτα άσχετο. Ο Χριστός πήγαινε στους αγρούς, στη θάλασσα, στα καΐκια των αγράμματων μαθητών του. Και είχε αγάπη. Λέγεται ότι αγαπούσε υπερβολικά τον Ιωάννη τον αγαπημένο του μαθητή. Οι μαθητές πάλι Τον αγαπούσαν. Και λέει ο Πέτρος «εγώ θα πέσω και στη φωτιά». Και του λέει ο Χριστός «Πέτρε, μη λες μεγάλες κουβέντες». Μετά, όμως, όλοι την έκαναν πραγματικότητα αυτή τη μεγάλη κουβέντα, γιατί σχεδόν κανένας απόστολος δεν πήγε από φυσικό θάνατο.

Η αγάπη εκφράζεται στην αγιογραφία με το φως. Δεν είναι ακριβώς συμβολισμός, γιατί ο συμβολισμός μας πάει κάπου αλλού. Είναι μία αμεσότητα εκείνη την ώρα. Δηλαδή ο Πατήρ αγαπά τον Υιό και Τον φωτίζει. Ο Υιός αγαπά τον άνθρωπο και τον φωτίζει. Αυτό μπορούμε στα συναισθήματά μας να το πούμε ότι όταν σε αγαπάει η μητέρα σου ή ο αγαπημένος σου σε χαριτώνει, σου φέρνει χαρά. Ενώ όταν περνάει αδιάφορα ή δεν σου κάνει ένα χάδι ή ένα κομπλιμάν, σε στενοχωρεί. Αυτό που είναι χαρά στα συναισθήματα των ανθρώπων στη θεία κατάσταση εκφράζεται όχι συμβολικά, αλλά με έναν τρόπο διαδικασίας της ζωγραφικής. Η διαδικασία της ζωγραφικής είναι τέτοια που φωτίζουμε. Πρώτα φτιάχνουμε τον προπλασμό και μετά παίρνουμε φωτεινά χρώματα και φτιάχνουμε το μάγουλο ή τη μύτη κ.ο.κ. Το φως υποστασιάζει τα μη υπάρχοντα όντα. Δηλαδή, ο μακαριστός Ιωάννης Περγάμου (Ζηζιούλας) έλεγε ότι το σκοτάδι του προπλασμού είναι το προκτισιακό μηδέν, το μηδέν πριν την κτίση, προτού να δημιουργήσει ο Θεός το σύμπαν. Και έρχεται τώρα το φως που είναι η αγάπη του Θεού και λέει «Γενηθήτω ο άνθρωπος». «Γενηθήτω ο Αδάμ και η Εύα». Και αυτό διαμορφώνει μία ζωγραφική όπου δεν υπάρχει θανατίλα. Εικαστικώς. Φουσκώνουν τα πόδια, τα χέρια, έχουμε, όπως λέγεται στα γαλλικά «pleines formes», έχουμε καμπύλες γραμμές. Τα περιγράμματα είναι καμπύλα. Είναι όλα φωτισμένα. Δεν υπάρχει τίποτα μισοφωτισμένο. Είναι όλοι βγαλμένοι μπροστά από τα σπίτια. Στον Μυστικό Δείπνο δείχνουμε το σπίτι όπου φάγανε, αλλά αυτοί σαν να έχουν βγάλει στην αυλή το τραπέζι. Και με τον τρόπο αυτό μπορούμε να πούμε ότι είναι σαν ένα αλληλοδόσιμο αγάπης που εκφράζεται μέσα από το φως. Και τα σπίτια είναι φωτισμένα, και τα δέντρα είναι φωτισμένα. Δείτε δέντρα σε μια εικόνα. Ας πούμε στην Ανάληψη είναι σε ένα δάσος. Στην προσευχή του Χριστού στη Γεθσημανή είναι στο δάσος των ελαιών. Ένα ένα φυλλαράκι είναι φωτισμένο, αλλά και όλο το δέντρο είναι φωτισμένο.

Με αυτόν τον τρόπο που φωτίζονται τα πράγματα στην εικόνα η φύση παίζει πρωταρχικό ρόλο, αλλά φωτιζόμενη. Το χρώμα είναι φωτισμένο. Οι σκιές είναι χρωματισμένες σκιές. Το έχετε σκεφτεί αυτό; Αυτό το ανακάλυψε ο ιμπρεσιονισμός το 1880. Και ο χριστιανισμός το είχε βάλει στις εικόνες από τον 4ο αιώνα, όταν ο Μέγας Κωνσταντίνος τους επέτρεψε να αρχίσουν να χτίζουν εκκλησίες και άρχισαν να κάνουν ψηφιδωτά, όπως της Ραβέννας, της Σάντα Μαρία Ματζιόρε. Είναι ένα φως ανέσπερο, δεν δύει ο ήλιος, αλλά είναι ένα φως που λάμπει και καταυγάζει τα πάντα.

Όταν τραβάω τα πράγματα στα άκρα, λέω «δεν υπάρχει σχέδιο». Δώστε μου ένα μαύρο σανίδι, θα του ρίξω εγώ το φως και φωτίζοντας το περιβάλλον και το μέσα και αφήνοντας στα ενδιάμεσα το μαύρο θα έχει σκιαγραφηθεί ο εικονιζόμενος άγιος. Όμως, υπάρχουν ασκήσεις επί χάρτου που γίνονται. Ο κάθε εικονογράφος δεν παύει να είναι ζωγράφος και πορτρετίστας. Φτιάχνει το πορτρέτο του Χριστού. Αλλά ένα πορτρέτο που είναι μετά την Ανάστασή Του. Δεν τον φτιάχνει την ώρα που σταυρώνεται και πέφτουν τα αίματα και σβήνει το φως και λέει «Θεέ μου, με εγκατέλειψες». Τον ζωγραφίζει την ώρα της θείας δόξης, όπως στο Θαβώρ και στην Ανάσταση. Επομένως, στις ασκήσεις επί χάρτου ο αγιογράφος θα δει εσένα, τον άλλο κ.ο.κ. και θα κάνει πρόβες σχεδίασης, σκιτσαρίσματος. Εκεί δουλεύει η σκιά, οι νόμοι της φύσεως. Αλλά όταν αναλαμβάνει τη σοβαρή ευθύνη τον άνθρωπο να τον ανεβάσει στο επίπεδο του καθ’ ομοίωσιν ότι γίνεται όμοιος με τον Θεό και, επομένως, λάμπει σαν Χριστός. Οι άγγελοι που ήταν στον τάφο του Χριστού και είχαν κυλίσει τον λίθο που ήταν μέγας σφόδρα και δεν μπορούσε ο άνθρωπος να τον κυλίσει ήταν ενδεδυμένοι εν εσθήσεσι αστραπτούσαις. Αυτό ο ζωγράφος θα περάσει από την άσκηση της σχεδιάσεως. Ή θα δει κάποια μοντέλα, αλλά όχι αυτά που οδηγούν σε μια ετοιματζίδικη φόρμα, απλώς θα μελετήσει. Μάλιστα οι αρχαίοι Έλληνες δεν βάζανε μοντέλα, έτσι έχει μείνει από τους ειδικούς. Έφτιαχναν το άγαλμα εκ του φυσικού και είχε όλες τις λεπτομέρειες, αλλά εξιδανικευμένες. Εκεί το θείον ταυτιζόταν με το ιδανικό της ιδέας. Αλλά οι ιδέες μας παραπέμπουν στο παρελθόν, ότι το ωραίο υπάρχει από πάντα. Στον Χριστιανισμό ο Χριστός είναι το αναπάντεχο, το μέλλον, ενώ φιλόσοφοι όπως ο Σωκράτης επικέντρωναν στο παρόν και το παρελθόν. Βλέπουμε τη στάση του λεωφορείου, βλέπουμε στο λιμάνι να βγαίνουν από το πλοίο άνθρωποι, βλέπουμε στα πάρτι ανθρώπους να χορεύουν. Στα Ταμπούρια, όταν ήμουν μικρός, ήμασταν σε ένα πάρτι και ανοίγω ένα παράθυρο και βλέπω έναν γάιδαρο. Είχαν μέσα σε ένα δωμάτιο έναν γάιδαρο με ταΐστρα και ποτίστρα κι ενώ εμείς χορεύαμε τη μποσανόβα ο γάιδαρος μας κοίταζε με τα ωραία ματάκια τα ταπεινά. Να ξαναγυρίσουμε στο θέμα μας. Και ο γάιδαρος μπαίνει μέσα. Έχουμε το γαϊδουράκι και το βοϊδάκι στο σπήλαιο μέσα τη στιγμή που γεννιέται ο Χριστός και τον κρατάει αγκαλιά η Παναγία μητέρα Του. Και αυτός μετέχει του θείου φωτός. Είναι φωτισμένος με ένα δομικής φύσεως φως. Δομικής φύσεως εννοούμε ότι το φως στηρίζει. Και εγώ μπορεί να κάνω χίλια σχέδια με το μολύβι. Με ενδιαφέρει να βρω την ιδιαιτερότητα του κάθε προσώπου. Αυτό το έχουμε ανάγκη επειδή ζούμε στην τωρινή ζωή. Όμως η εικόνα που μας πάει στην άλλη ζωή σημαίνει ότι παίρνουμε το σχέδιο και στο μέτωπο θα βάλουμε φως, στη μύτη θα βάλουμε φως και θα το μεταμορφώσει σε μια ζωγραφική που δομεί με βάση το φως, με φωτοδομή. Και ο ρυθμός δεν είναι να δημιουργήσουμε άξονες πώς είναι τα πόδια που χορεύουμε και αυτό να δημιουργήσει τον ρυθμό. Ο ρυθμός είναι ότι πέφτει ένα άκτιστο φως σε όλη την κτίση και πάει στο πουλάκι που είναι πάνω στο κλαδί, στο κλαδί, στο φυλλαράκι, στα πλακάκια της αυλής, στο νερό που τρέχει στο ρυάκι, στο πρόσωπο του πατέρα, στο πρόσωπο του αγίου. Και αυτό εκφράζει και την κτίση ολόκληρη και ως κορωνίδα τον άνθρωπο και, κυρίως, ότι είναι αγάπη του ενός προς τον άλλο σαν να είναι μοναδικός και ανεπανάληπτος. Και για αυτό δεν παύει ποτέ να μας αγαπά ο Χριστός, ακόμη και να κάνουμε το μεγαλύτερο έγκλημα. Και τον ληστή τον πήρε στον παράδεισο. Άρα πάντα υπάρχει ελπίδα και ποτέ μην πεις ότι είσαι μόνος.